In a bold attempt to arrest the sluggish lethargy of my blogging, I thought it might be worthwhile to consider making a break with tradition. As such, I’m going to try talking about a non-Ciceronian aspect of Classical literature that’s been on my mind lately. One of the great challenges that annually confronts a Latinist like myself at the start of the academic year is the need to teach Homer. This staple of the Classics forms the basis of Oxford’s teaching for undergraduates facing up to their first set of public examinations (the dreaded Mods). In light of the notion that all Classical literature (if not all literature in general) is a series of footnotes to Homer, I’ve always been keen to present my new students with Homer as their first assignment.

This is good and enjoyable for them, but is it good for me? If I have any competence at all as a teacher and researcher of the Classics, it is as a reader of Latin literature. The problem isn’t just that Greek pushes me a little bit out of my comfort zone (although the disappearance of the ablative case never ceases to make my heart sing); the main issue is that I’m used to analysing written texts. That is to say, my day-to-day existence involves studying words that an author carefully chose two thousand years ago and committed to a page in order to make some point or other in a more or less interesting way.

Homer isn’t like this. Although what we have to work with may be a written document (say, a Loeb edition of the Odyssey or an Oxford Classical Text of the Iliad), these texts are only a transcription of something far more fluid – Homer’s epics were composed and received orally. That is to say, we are dealing with the mere shadows of the extemporized live recitations of Archaic Greek poets.

Just as we would miss something essential to free-form jazz if we studied it solely through a notated transcription of a live performance, in the same way we cannot expect to understand the Iliad if we just read the words on the page. Trying to convince your students to understand that the various nuts and bolts of an oral epic (the repeated epithets, the recurring set-scenes, the limited vocabulary) are not barriers to thinking about these poems as great literature is the task of the first few weeks of each Michaelmas term.

The trick is to move past the stage where they see these unusual technical features as necessary infelicities that the poet would have dumped had he been able to write. One needs to understand that these repetitive phrases are the poetry. There are difficult and easy ways of making this point.

One of the easy ways is to focus immediately on the little repetitive formulae that are used to introduce the main characters or major locations: “swift-footed Achilles”, “grey-eyed Athene”, “the wine-dark sea”. It doesn’t take much prompting for students to grasp that there is a clear advantage to identifying certain gods and heroes with certain fixed epithets: it situates them in an accumulated literary history; it allows us to plug these figures into much larger networks; it means that the poet can subtly draw on larger traditions that orbit these archetypal characters.

Part of what makes this easy is the fact that we are, in fact, very used to this technique being used in folklore and fairy tales. Think of the “big, bad wolf”. A story-teller only has to mention these three words and they can rely on their audience already having a strong impression of who this character is; they can conjure up a vast array of stories about this villain from Red Riding Hood, to the Three Little Pigs, to the first series of the revamped Doctor Who.

Really finding the poetry in these repetitions, though, means going further than just looking at the epithets. This is the point at which a Big Idea comes in: J. M. Foley’s ‘Traditional Referentiality’. Traditional Referentiality posits an audience that is fully aware of the whole tradition in which the oral poet is working; they know the other stories in the epic cycle; they know that the events of the Iliad will eventually be followed by the Odyssey and that they were preceded by a whole series of poems that have not survived antiquity. Moreover, the audience knows how these stories were narrated and how the various scenes in each poem would be depicted.

As such, to quote Geoffrey Kirk:

“[E]ach of these accustomed phrases, as it is dropped from the listener’s consciousness, is clustered with the heroic past, ennobled rather than staled by its archaic associations, and thick with echoes of other contexts, other heroes, other actions in other islands, under the impulse of other but still familiar gods.”

G. S. Kirk, Homer and the Oral Tradition, pg. 6.

My Homerist colleague Adrian Kelly has a fine example of this (although he would hate the Latinized names I am using here). In the course of the indiscriminate slaughter that Achilles is meting out to the Trojans in the aftermath of his beloved Patroclus’ death, he comes to fight Aeneas. The fight starts badly for Aeneas and the audience has by this point got a pretty good idea about what to expect when a Trojan comes up against a raging Achilles. In the middle of the fight, however, Aeneas picks up a rock to hurl at Achilles (Iliad 20.281ff.). This should cause the audience some surprise: in the course of the poem, the act of picking up a rock as a weapon has always marked a decisive turn of the tide of battle in favour of the rock-wielder. This puts the audience off their footing, suddenly the outcome of the fight looks a little more uncertain. Sure enough, the gods intervene to ensure that the fight ends with no casualties.

We can even push these echoes beyond the poem itself and see the bard making references to the traditions of other episodes in the cycle of epics that had been built up around the Trojan War. For example, book 2 of the Iliad sees a dispirited Agamemnon come close to calling off the whole Trojan War. Hera has to intervene to prevent this, ensuring that there wasn’t a “homecoming beyond fate” (ὑπέρμορα νόστος Il. 2.155). The word for homecoming (Nostos, as in nostalgia) must call to mind the Nostoi, another episode in the Epic Cycle recording the Trojan heroes’ troubled attempts to get home. Hera is intervening to make sure that the poet can continue to narrate the Iliad without having to skip ahead to a later chapter in the tale.

Let’s take one more simple example that would be accessible even to a fairly novice reader of Homer. Everyone knows that the Odyssey will end with Odysseus using a bow and arrow to slay the suitors who have been besieging his wife back home in Ithaca. So whenever the poet uses a conventional formula to describe Odysseus picking up a bow in any epic poem (such as the Iliad), the audience is reminded of how his story ends.

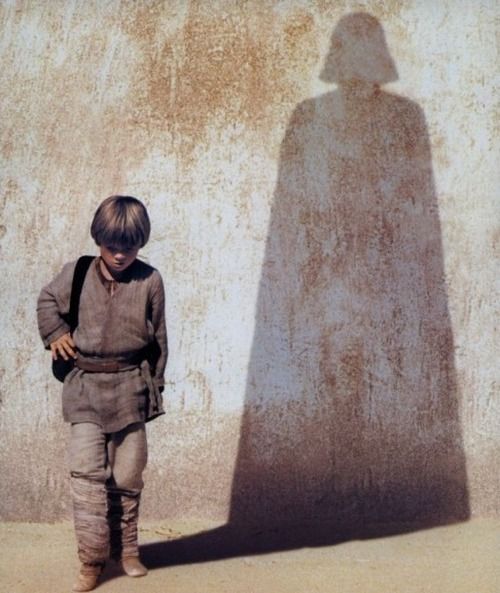

It’s not easy to think of an analogue for these effects in modern art. I suppose it’s somewhat like a particular character in a film series have their own theme music: when we hear it, we are reminded of other times we’ve heard that tune, and so we connect this moment with other incidents from that character’s life that we’ve had narrated to us. So think of hearing a snatch of Darth Vader’s theme music the first time you meet Anakin Skywalker as a boy on Tatooine.

ASIDE: It could be argued that Vince Gilligan achieves a similar effect in Breaking Bad through his consistent use of different colours in different scenarios. The reappearance of a certain colour in, say, Walter White’s wardrobe primes the audience to expect the scene to take on a certain tone, an expectation which the director can either gratify or frustrate:

https://tdylf.com/2013/08/11/infographic-colorizing-walter-whites-decay/

I would like to offer you one example of how Traditional Referentiality, as defined above, makes understanding the Iliad as an oral poem one of the most exciting experiences imaginable (at least for someone who grew up in a rural cul-de-sac).

In Book VI of the Iliad, the Trojan hero Hector, the greatest fully-human warrior in the poem, removes himself from the plain on which the Trojan War is being fought and enters the city he is defending. While he navigates his way through Troy, he meets a variety of characters who all in their own way explain why he is there and why he is fighting. He meets his mother Hecuba, his useless brother Paris, Helen (the semi-willing cause of it all), the wives of his troops (all clamouring for knowledge of their husbands’ well-being), and finally his wife and infant son, Andromache and Astyanax.

What makes Hector’s encounter with Andromache and Astyanax so moving is the fact that we know (and they know) that this is likely to be the last time he sees them – he is destined to die at the hands of Achilles at the end of the poem, setting in motion the chain of events that will eventually lead to the fall of Troy. The conclusion of this scene is particularly poignant. As Hector goes to kiss his baby son farewell, the infant is terrified of his father’s armour and recoils. The tension cast over of this scene by the spectre of Hector’s death is broken as mother and father laugh at their son’s confusion, while Hector removes his helmet and dandles his son for one last time.

Moments of shared humanity are rare in the Iliad, and even more rare are glimpses of a world beyond the battlefield, a world that the audience could recognize as part of their own lived experience.

To my mind, though, what makes the emotion of this episode almost unbearable is the fact that the audience knows the fate of baby Astyanax. Of all the atrocities committed in the sack of Troy, none provokes greater revulsion than the death of Hector’s infant son, hurled from the battlements by a marauding Greek warrior (by some accounts, the murder is committed by Odysseus himself).

We know that the sack of Troy was narrated as part of the cycle of Trojan epic poems (the lost Iliupersis – ‘The Fall of Troy’). I would like to consider this in light of what has been said above about Traditional Referentiality. That is to say, I would like to look at this scene in the context of the oral poet’s tendency to reuse certain phrases to link one moment in the Epic Cycle to another.

One and a half of the lines quoted above, I would like to suggest, could easily be reused by a poet narrating the Iliupersis:

ἂψ δ᾿ ὁ πάις πρὸς κόλπον ἐυζώνοιο τιθήνης | ἐκλίνθη ἰάχων… (Hom. Il. 6.467-8)

but back into the bosom of his fair-belted nurse the child | shrank shrieking…

I would like to suggest that as the audience hears these lines narrating how Astyanax recoils in terror from his loving father, the poet is aware that they are likely to have heard this phrase before, but in the grimly different context of that same child’s death.

The audience is given a stereoscopic image to digest: we witness the tender last moment shared by this wartime family, but we are simultaneously presented with the atrocity that will claim this child’s life. I can think of no other medium where this stereoscopic effect could be achieved with this degree of subtlety, without the artist’s intrusion seeming too obvious and heavy-handed.

Even Cicero can’t compete with this.